Why markets boom quickly but slide slowly

As each new set of property data is released, it becomes more obvious that some housing markets will be in for a rough ride. John Lindeman explains why property markets slide backwards slowly.

Many experts fail to grasp the reasons why property prices rise quickly during booms but slide backwards slowly during downturns.

Sales increase quickly when markets are hot, and prices shoot up because properties are snapped up as soon as they come on the market.

There are very few properties listed for sale, being outnumbered by large numbers of bidders who compete with each other to purchase, and as long as buyer demand remains high, a boom results.

When buyer demand falls, however, potential sellers dig in their heels and begin a waiting game, hoping that a buyer will turn up. The first signs of a slowdown in buyer activity are therefore not declines in sale prices, but a growth in the number of properties listed for sale and an increase in the time it takes to sell them.

Potential sellers tend to hang on and hope

When vendors still find it difficult to sell their properties, they may decide to change agents, increase their advertising budget, or even take their properties off the market altogether and wait until things improve.

Because no one wants to take a loss, or accept a lower sale price than they expected, only vendors who want to sell will reduce their asking prices when all else has failed and it is obvious that the market has slowed.

As asking prices slowly fall and the numbers of listings keep rising, sale prices start to decrease. Only vendors who really must sell will keep trying to find a buyer, and so the process repeats until finally a buyer is found. Such downward slides in sale prices can take a year or longer to play out.

But, when the bottom of the market has been reached, it may then take years before buyers want, or are able, to return to the market in sufficient numbers to kickstart the market back into growth once again.

Property prices slide slowly and then take years to recover

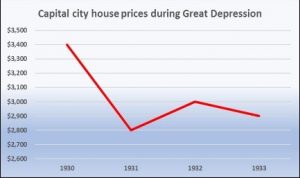

Here are some examples from history showing how this slow slide took place during the Great Depression, the sixties Credit Squeeze and the Global Financial Crisis.

The Great Depression started in 1930, marked by rapidly rising unemployment, falling incomes and bank failures. As the graph shows, house prices crashed by eighteen per cent over twelve months.

The property market then stagnated for several years, not fully recovering until after the Second World War, well over a decade later.

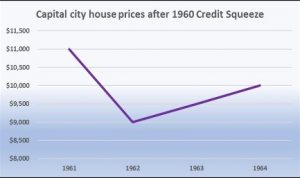

The 1960 Credit Squeeze was initiated by the Menzies federal government, concerned with the huge rise in hire purchase and housing finance debt.

It was short and sharp, but sent shock waves through the housing market for years after. Prices fell for one year after the squeeze, but did not recover for the next four years.

The Global Financial Crisis led to a slide in house prices during 2009 amid fears of a total housing market crash.

With its housing stimulus package, the Rudd government trebled the First Home Owner Grant. This lifted house prices by almost exactly the amount of the grant, after which prices fell once again for the next three years.

Demand side incentives only push up prices – temporarily

The Rudd First Home Owner Grant initiative demonstrates the total ineffectiveness of demand side buyer incentives such as buyer or owner grants and stamp duty concessions because all they do is increase the capacity of property buyers to spend more and push up prices in the process.

You might argue, as many politicians do, that if such concessions, grants and initiatives are limited to new properties, they will generate more housing supply. While it is true that more buyers will then be able to purchase new properties,the benefit is quickly eroded by rising prices, while existing buyer demand shifts away from new homes to existing homes, because they become comparatively more affordable.

Even worse, as pre-existing market conditions return, prices for new homes slide again and many first home buyers may find themselves worse off than before.